This blog is an edited version of a keynote CUSP director Tim Jackson gave at the 2013 Sea of Faith Annual Conference in Leicester. In outlining the philosophical foundation of a different approach to economics, this essay speaks as much to the financial crisis from 2008, as it does to the current health and economic predicament from COVID-19: “Out of crisis emerges this one completely rational insight, from a human perspective, that shows us that we are not the people the economic system says. When we begin to explore the idea that we’re not mindless, hedonistic, novelty-seeking, selfish consumers, then we can begin to unpack the interesting stuff. This is when we begin to see how altruism actually might have a role to play”.

I’m not going to give you a standard Prosperity without Growth talk. You can do that much more easily and much more fluently just by looking on the internet—there are hundreds of them out there somewhere on the internet. What I wanted to do here today was to talk about what I think is the philosophical foundation of a different approach to economics. I’ll talk a little bit about how economies are supposed to work, about why the model is wrong, and then I’ll try to build a different model, based on this very simple idea that locked within us is some kind of altruist, some kind of other-regarding behaviour.

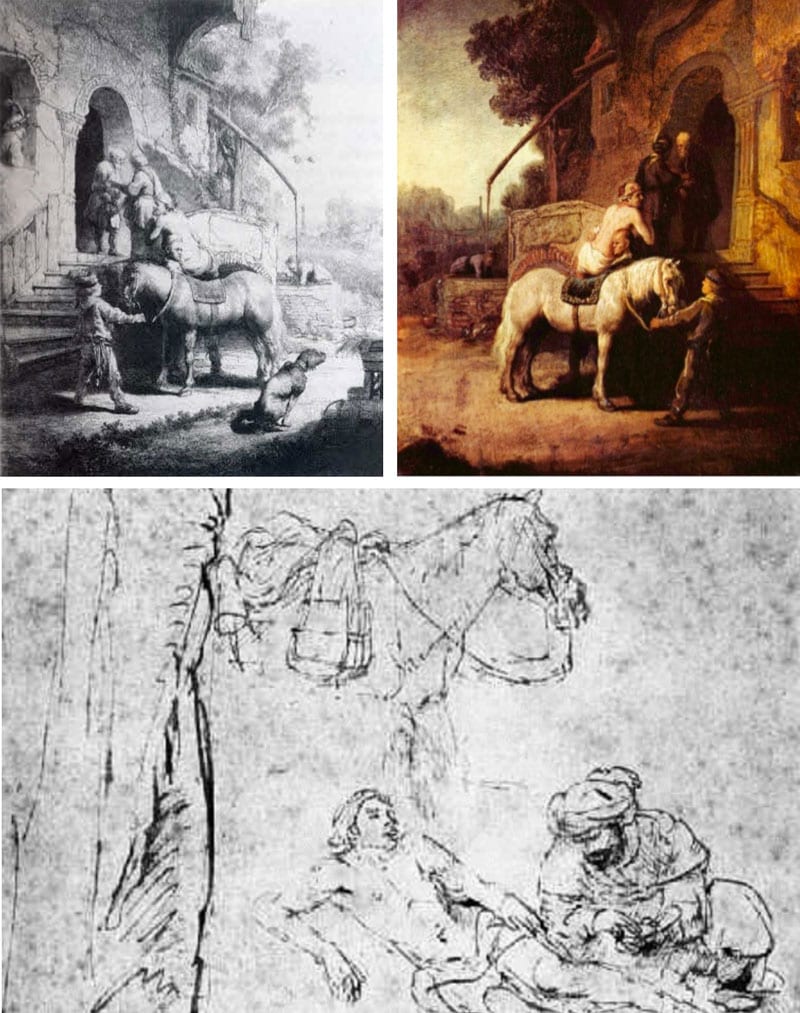

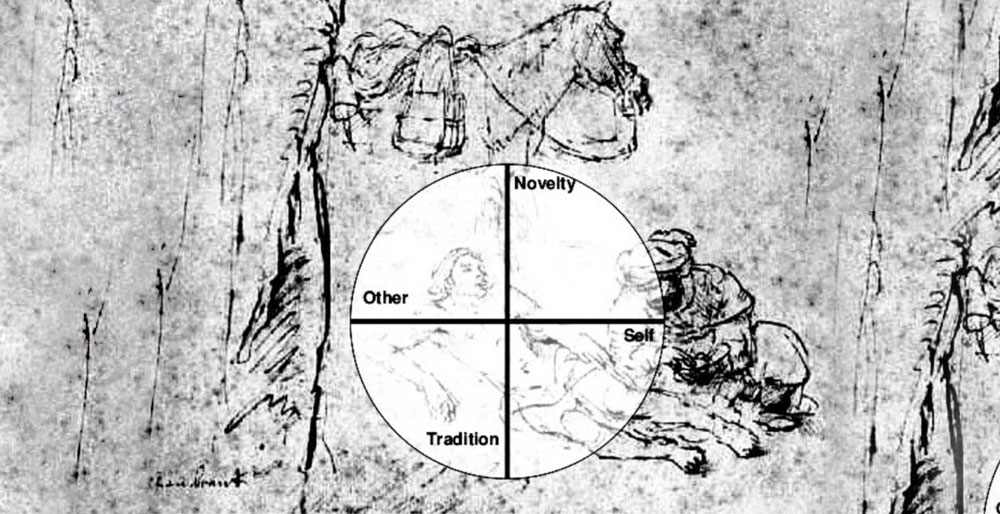

Lots of artists have been obsessed with the Good Samaritan. One was Rembrandt (Figure 1, top-left). I really love him as an artist—he’s such a fantastic social commentator. What you see here, actually, is a kind of a hierarchy of goodness. As with most Rembrandt pictures, on the very left, you’ll see somebody looking out of a window observing—Rembrandt’s observer is almost always there. At the top is the exchange of finance to create the ability for the innkeeper to sustain the man by the side of the road, and there, in the middle of the picture, you see this struggle of someone now being lifted off a horse, in the process of being taken into the inn, and on the bottom right hand corner, you see what? A dog crapping in the street! It’s a fantastic hierarchy, if you like, from the bestial to the altruist, and I love Rembrandt for this.

Here is Rembrandt again though (Figure 1, top-right), Rembrandt in contemplative mood, and the one that I really love (bottom), that to me inspires the idea of the altruist within. It is the roadside scene. It’s a moment of complete interiority, in that way that only Rembrandt can give, a relationship of giving from one person to another, in a space which disappears around you because what matters is the interaction between the two people. This is the quality that I want to put at the centre of an exploration of the economy.

Leaving art history aside for the moment, I want to talk briefly about the financial crisis which began with the Lehman Brothers’ collapse on 15th September 2008. It wasn’t entirely unforeseen, but it was nonetheless shocking, and it even prompted some wise words from some very wise people:

‘This has been an age of global prosperity; it’s also been an age of global turbulence, and where there’s been irresponsibility, we must now clearly say the age of irresponsibility must be ended.’ That was Gordon Brown in response to the collapse of Lehman Brothers. And, of course, economically, all sorts of very complicated things were happening.

What’s happened since 2000 and in the run-up to the crisis is a real change in economic conditions. In the summer of 2008, oil prices reached $147 a barrel, food prices caused riots on the streets of the poorest countries in the world, metal prices rose to highs unprecedented for over 100 years. And what was interesting about the crisis itself was that shares in those commodities began to fall and so you see this apparent collapse. This happens a lot in recessions. It’s a very common phenomenon, and most people think of it as a market correction, that things will then go back to normal. Well, they did, but they didn’t: they went back to ‘normal’ of just before the crisis; they didn’t go back to ‘normal’ of the last 100 years of economic experience when price falls were the expected norm. What you see after the crisis is a much faster ramp-up again of food prices, of metal prices, of oil prices, and a lot of volatility. So, this is an age of irresponsibility, but it isn’t quite the age of irresponsibility that Gordon Brown had in mind. It’s an irresponsibility built into the system itself.

In the wake of that crisis, one of the things that really came to the fore is the question of social justice. It should have come to the fore before that. But the crisis did bring social justice into the forefront of the conversations, for the very simple reason that it was the architects of the crisis who had benefited in financial terms from it, and it was also the architects of the crisis who benefited from the austerity programmes that followed it. Austerity politics was about propping up the financial sector again, trying to get it going, supporting its balance sheets, throwing money at the corporate sector in order to re-establish, so our politicians told us, the firm economic foundations for the growth-based society that we wanted in the future. But in order to afford that, we had to increase our sovereign debt, increase our deficit, and withdraw our social investment.

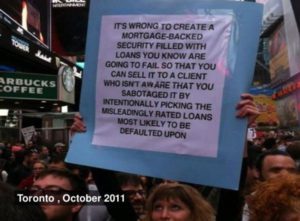

In 2011, in London, people were out in the streets in our own capital city, and many other capital cities around the world, actually setting fire to things and rioting because of the blatant injustice of austerity policy. It was triggered by a minor incident with the police. What came out of that crisis, what came out of the Occupy movement, what came out of the people on the streets in various countries protesting, is that sense of social injustice engendered by a financial crisis, in which those who were responsible benefited, and those who suffered from the crisis will be paying for decades through taxation and the sovereign debt. It was an interesting social moment when a lot of people recognised, perhaps for the first time, just how disingenuous, just how deceitful, just how unjust the financial system is.

Here is a piece of wisdom: ‘It’s wrong to create a mortgage-backed security filled with loans you know are going to fail, so that you can sell it to a client who isn’t aware that you’ve sabotaged it by intentionally picking the misleadingly rated loans most likely to be defaulted on.’ It is, if you think about it, fairly obvious that this is not quite the right thing to do, but it wasn’t obvious in the market at the time. It wasn’t obvious in the economy that we’d built.

At the heart of this system is what economists call the circular flow of the economy: firms make things for people, we are employed by firms, so we give them our labour and capital, they give us incomes in return, which is great because we can then spend them on more goods and services—circular flow. At one level, it’s pretty harmless: it’s just about the relationship between people—people doing things, making things, for each other, selling them to each other, a set of social relationships. The most interesting part of this relationship is what we do with the money that we don’t spend: we put it in banks. Banks then invest it in the economy. Much of that investment over the last years has been into increasing labour productivity, doing things more efficiently, more output with fewer people, year on year. The trouble with that, of course, is that if you do more with fewer people, year on year, unless your economy grows, you’re putting people out of work—unemployment is the victim of that. This pursuit of labour productivity almost drives us into having to grow our economies if we want to keep people working all the time.

It’s not all bad. Increasing productivity brings prices down and makes things more available to people. It also allows us to play one of our favourite games, the game of the new, the game of novelty. Where this gets really fascinating is the social psychology within us, because it turns out that we love new stuff: new cars, new homes, new gadgets, new phones, we love the new idea, we love the new experience—novelty plays into our psyche and we become consumers through this desire for novelty. Novelty plays into status competition, for example. If we’re ever tempted to forget that, then there are plenty of people prepared to remind us—to extend consumer credit, for example. And if we don’t think we’re getting enough through normal market processes, we can engage in what I like to call the casino economy, speculating on the commodities and the resources which we need in order to provide the goods and services with which we would like to pursue our search for the good life.

If we look at the lending data from 1972 to the beginning of this year, there is an extraordinary ramp-up, particularly of lending to households, not so much of a ramp-up in lending to firms to produce capital assets. But we also see this huge amount, which just wasn’t there at all before, of speculative commodity lending—the financial system lending to itself, the creation of evermore complex vehicles of lending and credit in order to expand the money supply. The economists will tell you expanding the money supply is a good thing because it drives growth. But the crisis came out of growth-based, growth-obsessed economics.

From 1993 to just before the crisis, personal debt rose until it was above 100% of the GDP for three years in a row, and household savings plummeted. It was really a very simple story. It was a story about ordinary people, about us, being persuaded to spend money we don’t have on things we don’t need to create impressions that won’t last on people we don’t care about.

At the same time, of course, this is a system driven by a kind of anxiety. The anxiety of the firm is that shareholders might take their capital elsewhere—capital will just flee to the places where they can do it. If you don’t engage in the game, if you don’t innovate, somebody else will, and you’ll be out of business. The anxiety within us actually was referred to by Adam Smith a couple of hundred years ago as ‘the desire to live a life without shame’, a very basic thing. In Adam Smith’s day, it was just a linen shirt that you needed to go out in public without shame, and now of course, it’s a whole big basket of commodities which we are persuaded are necessary for the good life. It almost convinces you, if you were to believe this story, if you were to believe the economics of it, that there is no altruist within, there’s nothing within—there is just a novelty-seeking, hedonistic, self-interested consumer. That’s all there is within. And yet, of course, everybody, in their heart of hearts, every philosopher, every poet, every artist, every ordinary human being knows that isn’t true.

And then you have a crisis, and a very strange thing happened in the crisis: the savings ratio shot up. It isn’t unknown—in fact, Keynes talked about it back in the Great Depression. He called it the ‘paradox of thrift’. Why is it a paradox? It’s a paradox because people really do change their behaviour during a recession: they save; they concentrate on necessity; they forego luxury; they think about security; they think about their family, their community, a little bit more; they want to hunker down and be a little safer. It’s a paradox because economies don’t like it. If you save during a recession, you just prolong the recession. It’s one of the reasons why the recession has gone on so long. People were so shocked into such a different kind of behaviour that they just didn’t want to get out on the high street and spend, despite all the social status that the advertisers told them it would bring them. What is fascinating about this to me is that it is, if you like, exactly a point at which the system shows us it is wrong: it is not in our interests. It is operating counter to our own instinctive behaviour. This is a system that is built around massively false assumptions about who we are, and when we show the economy who we are, the economy fights back and says you’re not allowed to be those people—you have to max out your credit card, you have to get back out on the streets and spend. But it’s fascinating because, within the economic system itself, and out of crisis, emerges this one completely rational insight, from a human perspective, that shows us that we are not the people the economic system says. When you begin to explore this idea that we’re not mindless, hedonistic, novelty-seeking, selfish consumers, then you begin to unpack the interesting stuff. This is when you begin to see how altruism actually might have a role to play.

Shalom Schwartz suggests that there is a tension within the human psyche between self-regarding behaviours and other-regarding behaviours. In Schwartz’s view, this is an evolutionary tension. In certain circumstances, it made a lot of sense to be selfish—fight or flight really does work when you’re under immediate threat in terms of survival—but other-regarding behaviour was absolutely critical to the success of building up social groups, of creating communities, of evolving as a social species. The point that Schwartz raises is that these things are always in a tension within us. Instead of a single idea of who we are as people, angels or devils, he says they’re both in there and they’re both operating—they both came through the evolutionary, the ancestral environment.

He sees a similar tension between novelty-seeking behaviours and tradition. He argues that novelty-seeking was also adaptive. When things are changing fast, it really helps to be able to pursue the new ideas, to create novelty. But we would never have evolved without longevity, without tradition, without custom, without conservation, without the groundedness that makes it possible to live in social groups.

Here is a much richer picture (figure above). Here is a real map of the human heart, if you like, which you might be able to use somehow to figure out what went wrong with economics. Economics created itself in the top right-hand quadrant of the human psyche. It deliberately built institutions to promote novelty and to regard selfish behaviour as the route towards the social good. What’s fascinating about this is that the change that’s needed is not about repression. It’s about recognising who we are, the whole circle of the human psyche, and about building institutions that nurture, that protect, that maintain these other neglected quadrants of the circle.

It sounds pretty simple to do. Of course, it’s horrendously complicated. At every turn, you’re told you have to have a growth-based economy. At every turn, the politicians tell you that jobs equal growth, and if you don’t have growth, you can’t have jobs. At every turn, you’re told that people must behave like this. At every turn, you’re told that politicians can do nothing. And at every turn it turns out to be wrong. At every turn there are alternatives.

Broadly speaking, I divide the building blocks of this new economy into four segments. One is around enterprise—what is enterprise doing in the new economy? Instead of chasing profits by maximising the throughput of material products and trying to sell them to people who don’t really need them, actually, enterprise is about service. It’s about delivering service—health, education, social care, leisure, recreation, gardens, public spaces, the maintenance of ecosystems, the building of communities. These are all service-based activities, often much lighter in material terms, because they’re not based on inherently material needs, than the stuff-based economy that is being thrown at us. And here is the most amazing thing of all: they are all employment-rich. Why? Because it makes no sense to ask the doctor keep seeing more patients. It makes no sense to ask the teacher to keep teaching bigger and bigger classes. It makes no sense to ask the London Philharmonic Orchestra to play Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony faster and faster each year. There are jobs to be had in this economy.

Investment is another key. Everybody knows that we have to have green technologies. We also have to invest in building this service sector. We have to invest in ecology itself because these natural assets are the ones on which we all depend in the long run for anything at all, and we need a slow, patient sense of capital in order to achieve this. That brings us, of course, to the biggest horror of all, the horror of money, the money-based economy. Where is this slow, patient capital going to come from in a financial system that was broken by selfishness running rampant, by very, very short-term targets, by bankers with huge bonuses and no responsibility, and governments who seemed to be in hock to them? Yes, money is complex. If you ask yourself the simple question ‘Where does money come from?’ after about a day, you realise you have no idea. After about a week, you realise that all the ideas on the table seem to conflict with each other. After several months, you are completely lost and despair of ever figuring out what money is and where it comes from. Then, eventually, if you read the right people, and think about it in the right way, you can actually fathom some of the answers to the point where at least it becomes believable that there are different ways of organising things than having commercial creation of money for 97% of our money supply, at commercial interest, whose interest belongs to a minority of individuals. Money is about the exchange of commodities, a medium of exchange. Money is about trading, about communicating. Money is about the social relationships between people, and yet the power of money creation has been handed over to a minority of people through the commercial interest created when banks create 97% of the money.

There are some very interesting things about the nature of the way this system works. One of them is that the things that the politicians told us about austerity in the wake of the crisis were not just badly wrong, they were fundamentally at odds with our understanding of the system. The politicians told us that we should be more frugal in relation to our personal savings, that businesses should have better balance sheet—they should protect their assets and reduce their liabilities. They told us that the public debt should be reduced. The only way you could possibly deliver that is to pump money into the financial corporations who were losing the money, and to cut most of your social investment as fast as you could, in order to try to achieve a public deficit that was as low as possible. Of course, George Osborne had our best interests at heart when he came up with that strategy! But actually, George, it’s complete rubbish—it is really economics of the worst kind.

You can only reduce private debt and public debt if you have a massively successful export economy. If you are Germany, you can do it. If you are Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland, or the UK, you have to think about the trade-offs between the public sector and the private sector, and since most of the public sector debts are being borne by the ordinary taxpayer, and most of the private savings are being accumulated by a minority of people, the inequality itself, injustice itself, is written into this equation. If you pursue a growth-based economics and austerity-based recovery policy, you are deeply indebted to the future and you’re creating massive social injustice.

‘It is well enough that the people of this nation do not understand our banking and monetary system, for if they did, I believe there would be a revolution before tomorrow morning.’ Any guesses who said it? No, it wasn’t Adam Smith. Henry Ford said it. Abraham Lincoln said very similar things about the ‘despotic power of money-creation’. Lots of good people have recognised that the money-based system that we’ve created is wrong, creates instability, and is inherently unjust. Here are just a few of the things that you can do about it.

Small scale community banks, for example, credit unions—the former Archbishop of Canterbury has just come out strongly in favour of credit unions and harangued Wonga and pay-day lenders for the horrendous social injustices they create. Small scale ideas, in the middle of the institutional sector, present huge possibilities for restructuring pensions and insurance, for example.

Then, the macroeconomic level, which we all love to talk about and debate over. And of course, we understand completely what quantitative easing and hypothecated transaction tax mean! Actually, what they mean is that there are other possibilities. We do not have to accept the power, the commercial power given to banks to create money at interest. We do not have to accept that the state has to borrow from those commercial banks, from that commercial lending market, in order to have people in jobs, in order to have people in health, in order to have kids in a school, in order to build communities. States are in hock to the commercial interests of a minority, and that has to be recognised as unjust.

There is a way—there are several ways—and they’re even beginning to be talked about, post-crisis, to change this money-based system. One of them is called the Chicago Plan, which was developed by Irving Fisher, back at the time of the Great Depression. It was a simple replacement of a fractional reserve system with a full reserve system. Recently, this idea has been revived. Who has it been revived by? Greenpeace? The New Economics Foundation? The Archbishop of Canterbury? No. The International Monetary Fund has a working paper on the Chicago Plan.

My point here is just to demonstrate that not everything that came out of the crisis was bad. There was recognition that the financial system could be other, and this to me is the point at which we should give no room for manoeuvre at all to the politics of austerity, because there are alternatives. These alternatives, in my view, are not just about a green economy, not just about sustainability, but about social justice and about the stability of the existing financial system, and they’re there for the taking. How does altruism fit in to what I’m saying here?

In enterprise, it’s about service. It is about how we relate to each other and it’s also about the structure of those enterprises. Cooperative, non-profit forms of enterprise are actually more easily able to deliver this kind of service because they’re not demanding fast financial economic returns all the time.

In employment—a friend of mine likes to talk about the ‘amateur economy’, the economy where we do things really for love. ‘Amateur’ comes from the Latin word for ‘love’. We do things for love, we do things through care, we dedicate time to it.

In investment. Impact-investing, peer-to-peer investing, all have elements of altruistic behaviour, because often you’re foregoing the highest possible returns in favour of something which you see as having social good. It’s enabling opportunities for people to do things that they care about.

And perhaps the most important part of all is the benefit of money creation. The financial benefit of money-creation is a public good. It should never have been handed over to selfish aims.

If talking about it doesn’t convince you, just start your own little collection of examples. Here are just a few of mine. There is Triodos Bank, that really does have an ethos of investing for good, and in which its savers accept lower rates of return in the knowledge that their money is going into projects in the health sector, in the education sector, in the energy sector in particular, which don’t trash the planet. Then there is Shared Interest. Shared Interest, as some of you may know, is the financial vehicle that enabled fair trade. Without Shared Interest, there would be no fair trade. It was the vehicle that shared the proceeds, the profits from the provision of traded goods, fairly with the producers of those goods in third world countries. Here’s an example that, again, is about 70 or 80 years old. This is the WIR Bank in Switzerland—wir is the German for ‘we’. This bank was put together on a very small scale in the 1930s to allow peer-to-peer lending between investors interested in building their economy at a time when it was almost impossible to get bank loans. They created, in the process, what is essentially an alternative currency in Switzerland, which is still there today. Thousands upon thousands of businesses rely on the WIR Bank.

I just want to finish with one of the three Greek words for love. Agape means the altruist within, prosocial behaviour as something that we could build into our social structure, and faith as a commitment device to get us there. I will leave you with this one lovely comment from Zia Sadar: ‘Prosperity can only be conceived as a condition that includes obligations and responsibilities to others.’ Pictured beautifully, as ever, by Rembrandt in his wonderful portrait of the altruist within.

This post first appeared on the CUSP website (May 2020).